There’s a note Charles Wright appends to his poem “Rosso Venexiano,” that I came across the other day, idly flipping through Oblivion Banjo, a massive Selected Works that will more or less forever anchor my otherwise meager reading pile. The note is simply this full excerpt from "An Interview with John Berryman,” published in a 1968 issue of the Harvard Advocate, fragments of which appear in italics in the poem itself:

INTERVIEWER: You said yesterday that to be a poet you had to sacrifice everything. Can you amplify on that, and tell why and how you first decided to make the sacrifice and be a poet?

BERRYMAN: Well, being a poet is a funny kind of jazz. It doesn't get you anything. It doesn't get you any money, or not much, and it doesn't get you any prestige, or not much. It's just something you do.

INTERVIEWER: Why?

BERRYMAN: That's a tough question. I’ll tell you a real answer, I'm taking your question seriously, This comes from Hamann, quoted by Kierkegaard. There are two voices, and the first voice says, "Write!" and the second voice says, "For whom?" I think that's marvelous; he doesn't question the imperative, you see that. And the first voice says, "for the dead whom thou didst love"; again the second voice doesn't question it; instead it says, "Will they read me?" And the first voice says, "Aye, for they return as posterity." Isn't that good?

November 19th, 2016, you learn about a death in the family. Of course, you are at a football game. Michigan is down 7-3 at the half to hapless Indiana, managing all of 64 yards on the ground, not much more through the air. By the time they’re down 10-6 late in the third quarter, one hundred thousand other people look just like you, deep in thought, staring off into the middle distance, mouths set in something that is neither a frown nor a smile. How strange that a look of anxious entitlement brought about by football’s most obnoxious memento mori—the chance at reaching, well, not quite Football Armageddon II the next week vs. Ohio State, but Football Tel IX or X or so, starting to slip away—just looks like grief.

Until it doesn't. De’Veon Smith does his thundering buffalo gallop into the endzone a couple of times, the game is effectively won, and everyone around you is joyous, alive. It’s cold, with stray flurries. “Oh well, just kidding, you’re not that mortal, after all,” the trickster football gods shrug, shining their favor upon a team that almost always wins, anyway. And once again all are set on Via Maris, and the summit is back in full view. Just your face remains unchanged.

You come back to your awareness somehow still caught inside a dream. Because snow is now falling in thick, impossible curtains. The field is white, blurry. There’s a mass bellowing of “Let It Snow,” but that’s a bit too saccharine for you, so you look up, all the way up, until the lights of the press box behind you are almost on top of your field of vision, and all you see is the undulating astral plane. Crystalline stars looping through black infinity. You hear nothing. “Behold, I show you a mystery; We shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye.”

Whenever I have to think about Charlottesville, a place I’ve never been, I think about Charles Wright. The American poet from Tennessee taught at the University of Virginia from 1983 until his retirement in 2010. While he is widely acclaimed, has served as Poet Laureate, won the major awards, I don’t believe he is someone you will have come across much in the American public unless you happen to read a lot of poetry. I barely do that, myself. Wright’s poems are not exactly accessible, either, which is a hard sell for a discipline colloquially understood to be always already inaccessible—I happen to find this reputation rather infuriating, but that’s for another time. “Almost nothing ever happens in a Charles Wright poem,” the poet and critic David Baker admits. “This is his central act of restraint, a spiritualist’s abstinence.” This resistance to action and commitment to the image is in part why Wright is maybe unfairly called (though he does not shy from it) a “landscape poet.”

Though landscape dominates Wright’s work, it’s a medium, a map but not the territory of meaning. In 1998 he published Appalachia, the final book of his “trilogy of trilogies” which he refers to in toto as “The Appalachian Book of the Dead.” In a reading he gave in May of 2004 at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, he described the project this way:

I've been working on this, oh God, this project for twenty-seven years, just book after book, I couldn't stop. It was awful. […] I got the idea for a Book of the Dead, which, as you will recall, if you remember reading of the Tibetan Book of the Dead, it's a bunch of mantras and amulets and sayings and pep talks spoken into the ear of the soon-to-be dearly departed who is a true believer and knows where he's going. And I thought, Well, I can do that, as long as I'm not the one whose ear is being whispered into. So I wrote some Books of the Dead.

For Wright, these “sayings,” really more like fragments and half-finished ideas, are wrung from the landscape itself. And by landscape, we don’t mean Yosemite or the Mediterranean (though Wright often, in his poems, returns to Venice, where, stationed with the U.S. Army, he discovered Pound’s Cantos and began writing); we just mean, often, Charlottesville. More succinctly, we mean his backyard.

In that 1998 collection is this poem—

American Twilight

Why do I love the sound of children's voices in unknown games

So much on a summer's night,

Lightning bugs lifting heavily out of the dry grass

Like alien spacecraft looking for higher ground,

Darkness beginning to sift like coffee grains

over the neighborhood?

Whunk of a ball being kicked,

Surf-suck and surf-spill from the traffic along the bypass,

American twilight,

Venus just lit in the third heaven,

Time-tick between "Okay, let's go," and "This earth is not my home."

Why do I care about this? Whatever happens will happen

With or without us,

with or without these verbal amulets.

In the first ply, in the heaven of the moon, a little light,

Half-light, over Charlottesville.

Trees reshape themselves, the swallows disappear, lawn sprinklers do the wave.

Nevertheless, it's still summer: cicadas pump their boxes,

Jack Russell terriers, as they say, start barking their heads off,

And someone, somewhere, is putting his first foot, then the second,

Down on the other side,

no hand to help him, no tongue to wedge its weal.

“There is one glory of the sun, and another glory of the moon, and another glory of the stars; for one star differeth from another star in glory.” This is 1 Corinthians 15:41. Virginia head coach Tony Elliott went out in search of the verse, trusting he’d find fated, intentional symmetry there.

It’s maybe self-evident why the final week of the regular season is replete with regional, often inter-state rivalries. The vestigial hatred gets sublimated into a kind of homecoming. One of these homecomings, the Commonwealth Cup, won’t take place this weekend. Elliott coaches a football team suspended in grief, with two games left on the schedule that will never take place. They were not meant to be played without junior receiver Lavel Davis Jr., junior receiver Devin Chandler, and junior linebacker DeSean Perry. 1, 15, and 41 in your game program, their feet now set down on the other side. Their teammates, many still teenagers, gathered for a memorial on November 19th, the day they were supposed to be somewhere else, doing something we watch to pass the time, and were already speaking of them as guiding stars in the firmament.

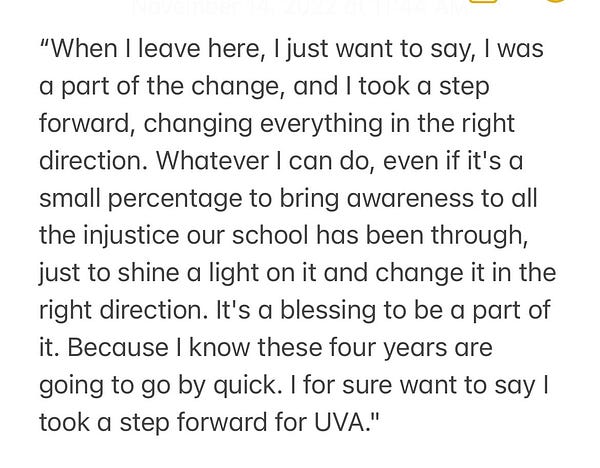

Davis Jr. was a member of the Groundskeepers. Formed in 2020, the group took its name from “The Grounds” that form the University’s campus, a campus built by slaves, and where, on August 11th, 2017, a group of torch-bearing white nationalists gathered and chanted, “you will not replace us.” The Groundskeepers’ first initiative was encouraging the university and wider Charlottesville community to, on their own time, take a ceremonial walk to the Memorial for Enslaved Laborers. The route would begin at the corner of E. Water St. and 4th St., where, on August 12th, 2017, one of those same torchbearers murdered counter-protestor Heather Heyer. The Groundskeepers was founded by Davis Jr.’s position coach, former Virginia quarterback Marques Hagan, who witnessed the events surrounding the Unite the Right rally firsthand. When Tony Elliott was hired after the resignation of Bronco Mendenhall, Hagan was the only coach he retained.

At the memorial, Eliott alluded to the verse after 1 Corinthians 15:41, which reads: “so also is the resurrection of the dead. It is sown in corruption, it is raised in incorruption.”

November 19th, 2022, there is a moment of silence. You are at a football game. Michigan is only up 7-3 by the half, their star running back is shelved after taking a helmet to the knee full speed. By the time they’re down 17-10 late into the third quarter, you look like one hundred thousand other people, deep in thought and staring off into the middle distance, mouth set in something that is neither a frown nor a smile. How strange that a look of anxious entitlement brought about by football’s most obnoxious memento mori—the chance at reaching Football Armageddon II next week vs. Ohio State, slipping away—is also, somehow, a look of relief. For you, at least, in this moment. This is how you wanted to feel, how you missed feeling. You’re actually enjoying this.

Jake Moody drives the game-winning field goal right down the middle. Everyone around you is alive. There’s a mass bellowing of “Moody, Moody,” and you join in. It’s cold, overcast now. The trickster football gods shrug, shining their favor upon your team, which almost always wins, anyway. You know they are just the lesser demiurges, and that their memento mori has all the heft of a carnival token.

After everyone leaves, you hang back in the stadium, alone. It’s cold, little cyclones of wax paper and napkins appear and dissipate in every other section. You make your way further down toward midfield. You watch the Marching Illini trickle down single-file onto the field from the back row behind the south endzone to eventually join ranks with the Michigan Marching Band and play, as they always do, to a sparse crowd of band families. After their respective fight songs, they play music from a famous film, and you head back up the steps and into the concourse, emptier than you’ve ever experienced. The wind is picking up, stray flurries. The band’s music fades. You’re spared, though deeper down, now, you want to be bruised, picked clean.

And the wind says “What?” to you. “And the stars start out on their cold slide through the dark. / And the gears notch and the engines wheel.”

Happy Thanksgiving. As for a preview of The Game, I’ll give the last word to Bill Bonds.

This is Prettyman, a newsletter about consuming college football. You can subscribe.

Notes: this week's title is borrowed from Charles Wright’s poem of the same name.